from Cancer Nutrition and Recipes For Dummies

"Spices and herbs have long been used

for medicinal purposes, such as fighting indigestion and other digestive

problems. Although science is uncertain about the direct benefits of

consuming certain spices and herbs with regard to protecting against and

fighting cancer and its side effects, their indirect beneficial effects

may be more easily recognized.

One such effect is their unique flavor profile, which ranges from strong to mild, with only small amounts needed to create a whole new taste sensation. When cancer-related loss of appetite and taste changes occur, which can lead to undesirable weight loss, adding herbs and spices to your cooking may help stimulate your taste buds and reinvigorate your appetite.

One such effect is their unique flavor profile, which ranges from strong to mild, with only small amounts needed to create a whole new taste sensation. When cancer-related loss of appetite and taste changes occur, which can lead to undesirable weight loss, adding herbs and spices to your cooking may help stimulate your taste buds and reinvigorate your appetite.

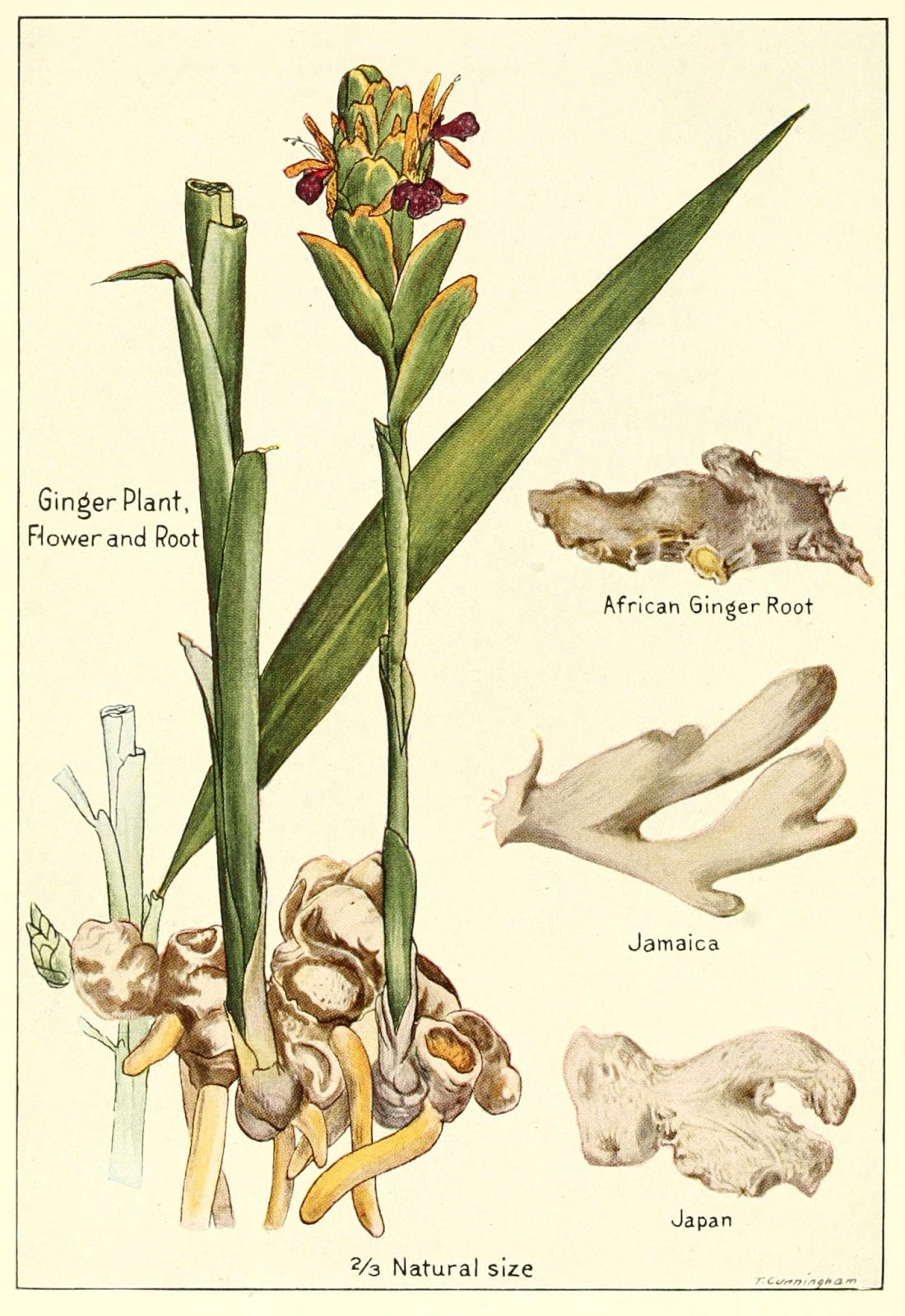

Ginger

Ginger has long been used in folk medicine to

treat everything from colds to constipation. Ginger can be used fresh,

in powdered form (ginger spice), or candied. Although the flavor between

fresh and ground ginger is significantly different, they can be

substituted for one another in many recipes. In general, you can replace

1/8 teaspoon of ground ginger with 1 tablespoon of fresh grated ginger,

and vice versa.

Consuming ginger and ginger products, in addition to taking any anti-nausea medications as prescribed, may provide some comfort for a queasy stomach during cancer treatment. |

Rosemary

Rosemary is a hearty, woody Mediterranean herb

that has needlelike leaves and is a good source of antioxidants. Because

of its origin, rosemary is commonly used in Mediterranean cooking and

you’ll often see it included as a primary ingredient in Italian

seasonings. You can use it to add flavor to soups, tomato-based sauces,

bread, and high-protein foods like poultry, beef, and lamb.

Rosemary may help with detoxification; taste changes; indigestion, flatulence, and other digestive problems; and loss of appetite. Try drinking up to 3 cups of rosemary leaf tea daily for help with these problems. |

Turmeric

Turmeric is an herb in the ginger family; it's

the ingredient that makes many curries yellow and gives it its

distinctive flavor. Curcumin appears to be the active compound in

turmeric. This compound has demonstrated antioxidant and

anti-inflammatory properties, potentially protecting against cancer

development.

Turmeric extract supplements are currently being studied to see if they have a role in preventing and treating some cancers, including colon, prostate, breast, and skin cancers. Although results appear promising, they have largely been observed in laboratory and animal studies, so it’s unclear whether these results will ultimately translate to humans. |

Chile peppers

Chile peppers contain capsaicin, a compound

that can relieve pain. When capsaicin is applied topically to the skin,

it causes the release of a chemical called substance P. Upon continued use, the amount of substance P eventually produced in that area decreases, reducing pain in the area.

But this doesn’t mean you should go rubbing chile peppers where you have pain. Chile peppers need to be handled very carefully, because they can cause burns if they come in contact with the skin. Therefore, if you have pain and want to harness the power of chile peppers, ask your oncologist or physician about prescribing a capsaicin cream. It has shown pretty good results with regard to treating neuropathic pain (sharp, shocking pain that follows the path of a nerve) after surgery for cancer. Another benefit of chile peppers is that they may help with indigestion. Seems counterintuitive, right? But some studies have shown that ingesting small amounts of cayenne may reduce indigestion. |

Garlic

Garlic belongs to the Allium class of

bulb-shaped plants, which also includes chives, leeks, onions, shallots,

and scallions. Garlic has a high sulfur content and is also a good

source of arginine, oligosaccharides, flavonoids, and selenium, all of

which may be beneficial to health. Garlic’s active compound, called allicin, gives it its characteristic odor and is produced when garlic bulbs are chopped, crushed, or otherwise damaged.

Several studies suggest that increased garlic intake reduces the risk of cancers of the stomach, colon, esophagus, pancreas, and breast. It appears that garlic may protect against cancer through numerous mechanisms, including by inhibiting bacterial infections and the formation of cancer-causing substances, promoting DNA repair, and inducing cell death. Garlic supports detoxification and may also support the immune system and help reduce blood pressure. |

Peppermint

Peppermint is a natural hybrid cross between

water mint and spearmint. It has been used for thousands of years as a

digestive aid to relieve gas, indigestion, cramps, and diarrhea. It may

also help with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome and food poisoning.

Peppermint appears to calm the muscles of the stomach and improve the

flow of bile, enabling food to pass through the stomach more quickly.

If your cancer or treatment is causing an upset stomach, try drinking a cup of peppermint tea. Many commercial varieties are on the market, or you can make your own by boiling dried peppermint leaves in water or adding fresh leaves to boiled water and letting them steep for a few minutes until the tea reaches the desired strength. Peppermint can also soothe a sore throat. For this reason, it is also sometimes used to relieve the painful mouth sores that can occur from chemotherapy and radiation, or is a key ingredient in treatments for this condition. |

Chamomile

Chamomile is thought to have medicinal benefits

and has been used throughout history to treat a variety of conditions.

Chamomile may help with sleep issues; if sleep is a problem for you, try

drinking a strong chamomile tea shortly before bedtime.

Chamomile mouthwash has also been studied for preventing and treating mouth sores from chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Although the results are mixed, there is no harm in giving it a try, provided your oncologist is not opposed. If given the green light, simply make the tea, let it cool, and rinse and gargle as often as desired. Chamomile tea may be another way to manage digestive problems, including stomach cramps. Chamomile appears to help relax muscle contractions, particularly the smooth muscles of the intestines." |